Volume 11, Number 1

Vol. 11 No. 1 (2026)

About the Cover

Tea Table, 1907

Carlo Bugatti

(Italian, 1856–1940)

France, Paris

Medium: Inlaid wood (mahogany?), cast and gilded bronze mounts, inlays of ivory or bone, metal, and mother-of-pearl (marine mussels or pearl oysters)

Measurements: 71.5 x 67.1 x 41.3 cm (28 1/8 x 26 7/16 x 16 1/4 in.)

Leonard C. Hanna Jr. Fund 1991.45

DESCRIPTION

Carlo Bugatti’s 1907 Tea Table is a window into the designer's expressive imagination with its elaborate arches and fantastical imagery, something that appears throughout his furniture designs. Son of architect and sculptor, Giovanni Luigi Bugatti, Carlo Bugatti was born in Milan, Italy, in 1856. He studied at the Brera Academy in Milan and then the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris before returning to Milan to begin creating furniture in 1880.

Bugatti was inspired by North African, Islamic, and Japanese designs, and he heavily influenced the Art Nouveau movement. His furniture is heavily decorated, featuring inlays of exotic wood, copper and parchment, as well as mother of pearl.

Bugatti is the father of sculptor Rembrandt Bugatti, whose work now sells for millions, and automobile visionary Ettore Bugatti, who studied engineering and designed his own work of art in the manufacturing of the iconic Bugatti.

References

1 Tea Table. Carlo Bugatti, 1907. Cleveland Museum of Art. Accessed August 2025. www.clevelandart.org/art/1991.45

2 Carlo Bugatti. Bugatti.com. Web Archive. Accessed January 2026. https://web.archive.org/web/20100704202833/http://www.bugatti.com/en/tradition/history/the-bugatti-family/carlo-bugatti.html

3 Sansom, I. Great dynasties of the world: The Bugattis. The Guardian. Published April 8, 2011. Accessed January 2026. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2011/apr/09/bugatti-cars-jewellery-jeremy-clarkson

4 Carlo Bugatti. Wikipedia. Updated August 8, 2024. Accessed January 2026. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carlo_Bugatti

Volume 10, Number 2

Vol. 10 No. 2 (2025)

About the Cover

The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy), 1889

Vincent van Gogh

(Dutch, 1853–1890)

Netherlands

oil on fabric

Framed: 104.5 x 124.5 x 7.6 cm (41 1/8 x 49 x 3 in.); Unframed: 73.4 x 91.8 cm (28 7/8 x 36 1/8 in.)

Gift of the Hanna Fund 1947.209

DESCRIPTION

The Large Plane Trees, also known as the Road Menders at Saint-Remy, is an oil on canvas painted by Vincent van Gogh in 1889. The Large Plane Trees, which is displayed at the Cleveland Museum of Art, is one of two versions of a village street scene. A second version of the painting, The Road Menders, is part of the Philips Collection in Washington DC.

Van Gogh frequently made copies of his art, calling them répétitions. The Large Plane Trees is believed to have been painted first followed by The Road Menders, believed to have been created in a studio. The paintings provided the inspiration for the 2013-2014 exhibit “Van Gogh Repetitions” that brought together 13 instances of van Gogh’s artistic versioning. The exhibit appeared first at the Phillips Collection in Washington DC, which ran from October 12, 2013, to February 2, 2014, and then moved to the Cleveland Museum of Art in Cleveland, Ohio, which ran from March 2 to June 1, 2014.

The painting is a vibrant palette of autumn tones with energetic brushstrokes. The scene depicts local villagers at work repaving a street under towering trees in Saint-Rémy, known at the time as the Cours de l’Est, where van Gogh lived in a nearby asylum for the treatment of severe depression. During his stay, van Gogh’s physician allowed him to paint outside as part of his recovery.

References

1 The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy). Vincent van Gogh, 1889. Cleveland Museum of Art. Accessed February 2025. www.clevelandart.org/art/1947.209

2 The Road Menders. Vincent van Gogh, 1889. Phillips Collection. Accessed February 2025. https://www.phillipscollection.org/collection/road-menders

3 Vincent van Gogh, The Large Plane Trees (Road Menders at Saint-Rémy), 1889. Artsy. Accessed February 2025. https://www.artsy.net/artwork/vincent-van-gogh-the-large-plane-trees-road-menders-at-saint-remy

4 Adams H. Seeing Double: Van Gogh the Tweaker. New York Times. Published October 2, 2013. Accessed February 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/06/arts/design/seeing-double-van-gogh-the-tweaker.html

Volume 10, Number 1

Vol. 10 No. 1 (2024)

About the Cover

White-Ground Lekythos (Oil Vessel): Atalanta and Erotes, c. 500–470 BCE

Cleveland Museum of Art

attributed to Douris (Greek, Attic, active c. 500–470 BCE)

Ceramic

Overall: 31.8 cm (12 1/2 in.)

Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1966.114

DESCRIPTION

This White-Ground Lekythos painting is a ceramic vase attributed to the Greek artist Douris. It is one of several vase paintings that depict the Greek heroine Atalanta, who was known for both her speed and opposition to marriage.1,2,3 Atalanta is the subject of three Greek myths, one of which is “The Footrace.” In Greek mythology, Atalanta was abandoned by her father, who wanted a son, and was cared for by a she-bear until she was found and raised by a group of hunters. Atalanta grew to become a skilled huntress and opposed men generally and the idea of marriage.3

In “The Footrace,” Atalanta’s father demands she marry. She reluctantly agrees only if the suitor can beat her in a footrace,2,3. an ancient Greek prenuptial rite in which males competed for the hand of the woman.3However, in this footrace, Atalanta competes against the suitors herself. In versions of the myth, Atalanta is either the pursuer or the pursued.2

The lekythos on which Douris’ image is painted is a type of ancient Greek vessel used for storing oil. It appeared around 590 BCE decorated with black and occasionally red paintings.4 A later technique included a white-ground clay backing applied to the surface, a style that has been found in Athenian graves and therefore believed to be associated with funeral rites.2,4 The Greek perception of marriage as a metaphorical death is also well known.2 Therefore, in this depiction, Atalanta, who is racing away from love and marriage, as suggested by the shape of the vase, faces a metaphorical death if she is caught.2,3

In Douris’ White-Ground Lekythos, Atalanta races toward the right of the vessel, while looking back at Eros, the winged God of love, who is racing forward trying to crown her. Two more Erotes are present. In the end of “The Footrace,” Atalanta is tricked by her suitor and beaten. It is said they fall in love and the two go on to become great hunters together.3

Here, as three Erotes hem in on Atalanta, will love win?

References:

1 White-Ground Lekythos (Oil Vessel): Atalanta and Erotes, c. 500–490 BCE. The Cleveland Museum of Art. Accessed September 2024. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1966.114"

2 Barringer JM. Atalanta as Model: The Hunter and the Hunted. Classical Antiquity. 1996;15(1): 48-76. www.jstor.org

3 The Myth of Atalanta. Hellenic Museum. https://www.hellenic.org.au/post/the-myth-of-atalanta

4 Lekythos. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/art/lekythos

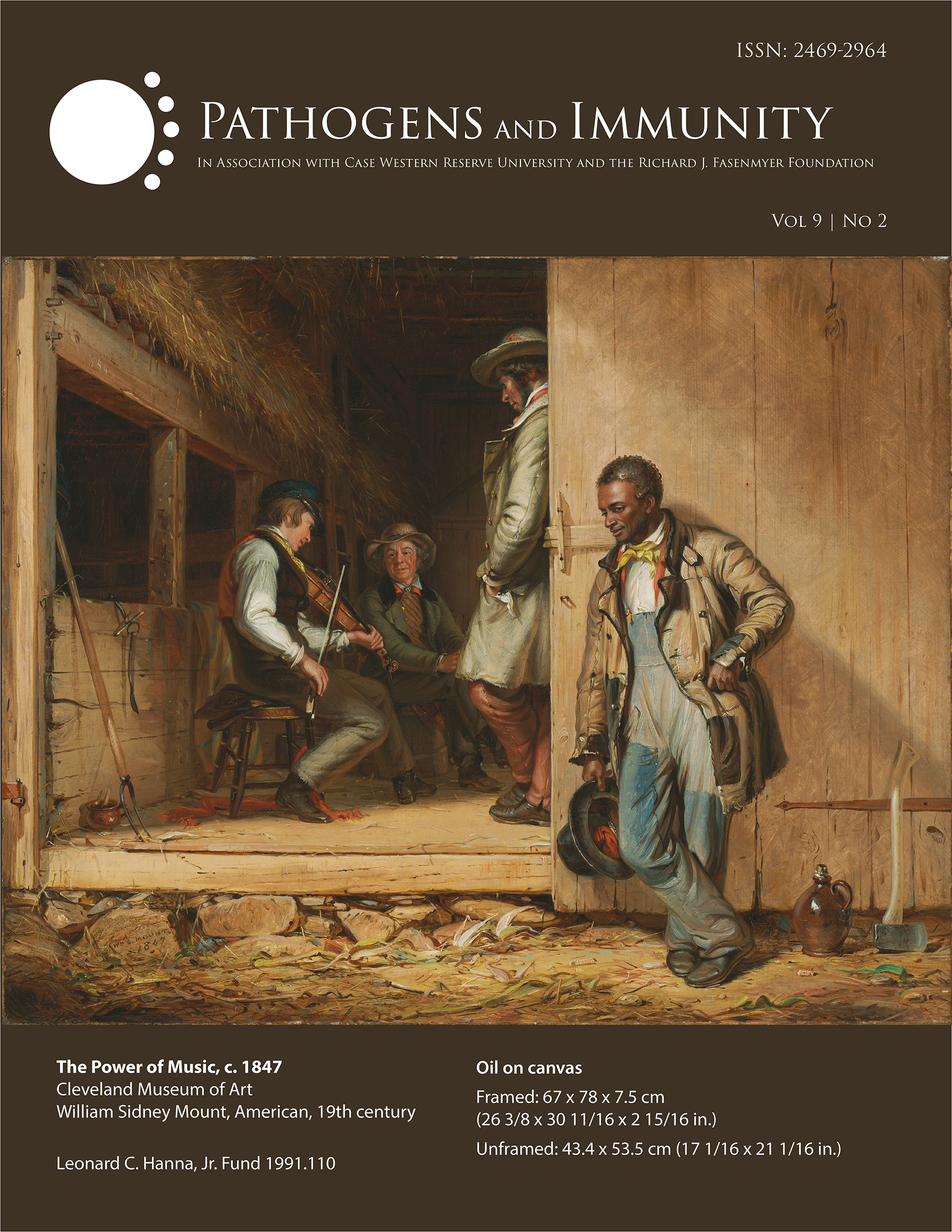

Volume 9, Number 2

Vol. 9 No. 2 (2024)

About the Cover

The Power of Music, c. 1847

Cleveland Museum of Art

William Sidney Mount, American, 19th century

Oil on Canvas

Framed: 67 x 78 x 7.5 cm (26 3/8 x 30 11/16 x 2 15/16 in.)

Unframed: 43.4 x 53.5 cm (17 1/16 x 21 1/16 in.)

Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 1991.110

DESCRIPTION

It is said that William Sidney Mount enjoyed creating scenes depicting everyday life in small-town America, which was the setting of his youth. “The Power of Music” is one of Mount’s most celebrated pieces and also his most rare.

The oil on canvas is set in rural Long Island before the Civil War and depicts an African American laborer standing outside of a barn, listening in on the music being enjoyed by several White men. In this way, Mount remarks on a shared humanity through music, while the separation of the men symbolizes the divisions in America during this time.

Though he led a trend in depicting everyday American life in his art, many of his contemporaries depicted Black Americans as caricatures, where Mount's portrayals, while still paternalistic, held more empathy.

References:

The Power of Music, William Sidney Mount, c. 1847. The Cleveland Museum of Art. Accessed June 2024. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1991.110

William Sidney Mount (1807-1869), The Power of Music. Arader Galleries. Accessed June 2024. https://aradergalleries.com/products/william-sidney-mount-1807-1868-the-power-of-music

Volume 9, Number 1

Vol. 9 No. 1

About the Cover

Nataraja, Shiva as the Lord of Dance, c. 1000s

Cleveland Museum of Art

South India, Tamil Nadu, Chola period (900-1200s)

Bronze

Overall: 113 x 102 x 30 cm (44 1/2 x 40 3/16 x 11 13/16 in.)

Base: 35 x 24 cm (13 3/4 x 9 7/16 in.)

Weight: 116.573 kg (257 lbs.)

Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund 1930.331

DESCRIPTION

The Nataraja sculpture is said to embody the Indian concept of cyclical time. The sculpture depicts the Hindu God, Shiva, whose cosmic dance symbolizes the creation and destruction of the universe. It was created in southern India during the Chola period (880-1279 CE).

While dancing within a circle of flames, Shiva holds in his back left hand the fire that will destroy the universe and simultaneously raises a drum in his back right hand, which refers to the relentless beat of time moving forward. With his front right hand, he signals not to be afraid; though with each step of his dance, he lands on a dwarfish figure that personifies ignorance from which he indicates liberation by pointing his front left hand to a raised left foot. The gestures are said to represent Shiva’s five activities: creation, protection, destruction, embodiment, and release.

Shiva’s dance became a metaphor for the cosmic dance of subatomic particles following the publication of an article titled, “The Dance of Shiva: The Hindu View of Matter in the Light of Modern Physics,” by physicist Fritjof Capra in which he described this parallel and which lead to his best-selling book titled, “The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism.” In 2004, a statue replica of this sculpture was given to CERN, the European Center for Research in Particle Physics in Geneva, by the Indian government, acknowledging the significance of the metaphor that CERN’s physicists regularly observe.

References:

Nataraja, Shiva as the Lord of Dance, c. 1000s. The Cleveland Museum of Art. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1930.331

Shiva as Lord of Dance (Ntaraja). The Met. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/39328#:~:text=As%20a%20symbol%2C%20Shiva%20Nataraja,never%2Dending%20cycle%20of%20time

Das S. Nataraj Symbolism of the Dancing Shiva. Learn Religions. Updated September 7, 2018. https://www.learnreligions.com/nataraj-the-dancing-shiva-1770458#:~:text=The%20Significance%20of%20Shiva%27s%20Dance,rhythm%20of%20birth%20and%20death

Fritjof Capra talks about his journey towards balancing science and spirituality. The Hindu. Published November 18, 2017. Updated November 20, 2017. https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/interview/fritjof-capra-talks-about-his-journey-towards-balancing-science-and-spirituality/article20550307.ece

Shiva’s Cosmic Dance at CERN. FritjofCapra.net. Published June 20, 2004. https://www.fritjofcapra.net/shivas-cosmic-dance-at-cern/

Nataraja. Britannica. Updated February 9, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nataraja

Volume 8, Number 2

Vol. 8 No. 2

About the Cover

The Holy Family with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Margaret, c. 1495

Cleveland Museum of Art

Filippino Lippi (Italian, 1457–1504)

Italy, 15th century

Tempera and oil on wood

Framed: 184 x 186 x 9.5 cm (72 7/16 x 73 1/4 x 3 3/4 in.); Diameter: 153 cm (60 1/4 in.)

The Delia E. Holden Fund and a fund donated as a memorial to Mrs. Holden by her children: Guerden S. Holden, Delia Holden White, Roberta Holden Bole, Emery Holden Greenough, Gertrude Holden McGinley 1932.227

DESCRIPTION

This painting is known as a tondo, which is Italian for “round.” This circular painting style became popular in Italy during the 15th century and was commonly created for settings such as private homes or palaces. This composition was commissioned by Oliviero Caraffa, Cardinal of Naples who likely selected the theme and the subject of the painting, which represents the divine motherhood, one of the most recurrent themes of Christian art from the period. The painting overlaps five figures with meticulously detailed still-life elements rich with symbolism and includes representations of classical architecture. The combination is said to reflect the artist’s interest in northern European painting and his interest in ancient Roman art and architecture.

Filippino Lippi was born around 1457 to painter Fra Filippo Lippi and a young nun named Lucrezia Buti. He first trained under his father and, following his death, he entered the workshop of Sandro Botticellio before going out on his own to become one of the most accomplished Renaissance painters of the late 15th century.

References:

Lippi F. The Holy Family with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Margaret, c. 1495. The Cleveland Museum of Art. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1932.227

Tondo. Encyclopedia Brittanica. https://www.britannica.com/art/tondo-art

Fliegel SN. Filippino Lippi's Holy Family. La gazzetta Italiana. Published January 2016. https://www.lagazzettaitaliana.com/history-culture/7922-filippino-lippi-s-holy-family

Lippi F. The Holy Family with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Margaret, c. 1495. Artsy.net. https://www.artsy.net/artwork/filippino-lippi-the-holy-family-with-saint-john-the-baptist-and-saint-margaret

Volume 8, Number 1

Vol. 8 No. 1

About the Cover

Café Wepler

c. 1908–10, reworked in 1912

(French, 1868–1940)

France, late 19th-early 20th Century

Oil on fabric

Framed: Framed: 91.8 x 132.7 x 13 cm (36 1/8 x 52 1/4 x 5 1/8 in.)

Unframed: 62.2 x 103.2 cm (24 1/2 x 40 5/8 in.)

Gift of the Hanna Fund 1950.90

Image Credit: Cleveland Museum of Art

DESCRIPTION

In this oil on fabric painting, artist Edouard Vuillard depicts a large brasserie restaurant on Place Clichy in the Montmartre district of Paris. It is composed of several rooms on different levels.

Vuillard’s initial work was strongly influenced by Japanese wood block prints, which revealed bright colors and vivid patterns. Also influenced by several post-impressionist painters, he became a prominent member of a group called the Nabis, whose artwork often featured bold patterns and bright colors on textured surfaces. Vuillard lived near Café Wepler, which was the Paris hangout for the group, frequented by artists like Pablo Picasso and Amedeo Modigliani. Today, the Wepler is still in business.

Over time, Vuillard’s colors became more subdued, reflecting a desire to mimic the lighting effects in symbolist theater as he developed his decorative art, creating a variety of decorative projects, including theater sets, wallpaper, textiles, ceramics, and stained glass.

Later in his career, he moved into interior decoration with his first major commissions, which included nine panels for the dining room of Alexandre Natanson and four decorative panels for the library of Dr. Henri Vaquez.

Sources:

Café Wepler. Edouard Vuillard 1908-1910, rewored in 1912. Cleveland Museum of Art. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1950.90

Café Wepler. (c. 1908–10). About the Artist. https://artvee.com/dl/cafe-wepler/

Auricchio L. The Nabis and Decorative Painting. The MET. Published October 2004. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dcpt/hd_dcpt.htm

Stamberg S. Vuillard: A Parisian Painter And His Jewish Patrons. NPR. Pulished June 19, 2012. https://www.wnyc.org/story/217353-vuillard-a-parisian-painter-and-his-jewish-patrons/

Volume 7, Number 2

Vol. 7 No. 2

About the Cover

Portrait of a Woman, possibly Elizabeth Boothby

1619

Cornelis Jonson (called Jonson van Ceulen)

(British, 1593-1661)

England, 17th century

Oil on wood

Framed: 93.5 x 78 x 5 cm

Unframed: 65.7 x 56 cm

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Noah L. Butkin, 1973.185

Location: 213 Dutch Painting

Image Credit: Cleveland Museum of Art

DESCRIPTION

In this oil on wood painting, artist Cornelis Jonson displays the stunning portrait of Elizabeth Boothby, the daughter of a 16th century prominent London merchant. Although painted in England, Jonson’s work reflects the traditions of Dutch portraiture. The period’s richness and detailed realism is reflected in the faux marble oval surrounding the portrait, the expensive lace that adorns the subject’s silk gown, the jewels in her hair, and the silver thread that hangs down from her neck. All of which are symbols of wealth and status. Note the exquisite detail of the lace and consider the attention and delicacy needed to make it so.

Cornelis Jonson received his art training in Amsterdam before returning to England where his style developed under the influence of the Flemish portraitist Daniel Mytens the Elder. He spent a decade as a portraitist for the English aristocracy. In 1632, he was appointed one of the official court painters for Charles I, becoming “his Majesty’s servant in the quality of Picture drawer.” He spent the last 20 years of his career in the Dutch Republic.

Sources:

Portrait of a Woman, possibly Elizabeth Boothby. Cornelis Jonson (called Jonson van Ceulen) 1619. Cleveland Museum of Art. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1973.185

Cornelis Jonson van Ceulen. National Gallery of Art. https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.26319.html

Discover the works of the Dutch Golden Age Painters. Google Arts and Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/discover-the-work-of-the-dutch-golden-age-painters/HgURuPe2Fz5CIw?hl=en

Volume 7, Number 1

Vol. 7 No. 1

About the Cover

Statuette of a Woman: "The Stargazer"

3000 BC

Early Bronze Age, Western Anatolia?, 3rd Millennium BC

Marble

Overall: 17.2 x 6.5 x 6.3 cm (6 3/4 x 2 9/16 x 2 1/2 in.)

Weight: 453.592 g (16 oz.)

Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund; John L. Severance Fund 1993.165

Image Credit: Cleveland Museum of Art

DESCRIPTION

"The Stargazer" is a small marble statue carved more than 5,000 years ago. It is one of only about 30 known to exist and is one of the earliest sculptures of the human figure in the Cleveland Museum of Art’s collection.

Stargazer is pure and simple in form with an oval-shaped head that looks up toward the heavens. Details carved into the stone are visible; however, painted features have been lost to time. The sculpture has no mouth, her nose is an elongated ridge, and her small, circular eyes are done in the slightest of relief. The figure can be identified as female by the incised triangular lines below the pelvic area. These same lines define the legs and stop at the feet, which appear to be held tightly together and are her narrowest point.

Thought to be from Western Anatolia, she is carved from a translucent marble that emulates a soft flesh when polished, which adds to the figure’s mystical quality. The Stargazer cannot stand on her own, suggesting that she may have been meant to be held or to lay down. The female form may be associated with fertility and abundance.

While it is not known how this object was used, her mysterious nature invites speculation. Her modernist form gives her a sense of timelessness as her upturned head draws attention away from herself to what is above and outside.

Sources:

Mikolic A. Statuette of a Woman: The Stargazer is a ‘must see’ at the CMA. Cleveland Museum of Art. Published February 1, 2019. https://medium.com/cma-thinker/statuette-of-a-woman-the-stargazer-is-a-must-see-at-the-cma-3d2d64115c7d

Statuette of a Woman: “The Stargazer” c. 3000 BC. Cleveland Museum of Art. Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1993.165

Volume 6, Number 2

Vol. 6 No. 2

About the Cover

Untitled

By Phyllis Sloane

Silkscreen on paper, 19.5 x 25”, 1979

Collection of the Artists Archives of the Western Reserve

Phyllis Sloane (1921-2009) was Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, grew up in Shaker Heights, Ohio, maintained a studio on Mayfield Road in Cleveland’s Little Italy for many years, and finally ended up in Santa Fe, New Mexico where a studio still stands preserved by her children. She was a prolific artist, and for more than 60 years, she explored a variety of mediums, print-making techniques and subject matters, producing thousands of works of art. Beginning with abstract painting in the 1950s and 60s, she moved to more representational works, including still life, city and landscapes, as well as the human figure during the last several decades of her career. She received many awards, including the 1982 Cleveland Arts Prize. Her work has been displayed at the Cleveland Museum of Art and across the United States in various private, corporate, and public museum collections, including the regional archival museum Artists Archives of the Western Reserve, which she co-founded in 1996.

“Art is a method of communication. … There has never been anything else I find as interesting or as fulfilling,” she wrote in a comment for the Artists Archives of the Western Reserve.

About Artists Archives of the Western Reserve

Founded in 1996 by Cleveland sculptor David E. Davis and eight additional prominent Ohio artists, the Artists Archives of the Western Reserve (AAWR) is an archival facility and regional museum located in University Circle, Cleveland, Ohio’s premiere cultural district.

The founding artists believed in the importance of preserving Ohio’s unique visual artistic heritage. So, AAWR preserves representative bodies of work created by Ohio visual artists and, through ongoing research, exhibition, and educational programs, actively documents and promotes this region’s cultural heritage for the benefit of the public.

AAWR maintains a representative body of each archived artist’s work as well as documentation of their lives and careers as Ohio-based artists. Accordingly, the AAWR records oral histories, catalogs exhibition materials, and collects related documents on Ohio artists.

For more information, visit www.artistsarchives.org

Volume 6, Number 1

Vol. 6 No. 1

Volume 5, Number 1

Vol. 5 No. 1

Volume 4, Number 2

Vol. 4 No. 2

Volume 4, Number 1

Vol. 4 No. 1

Volume 3, Number 2

Vol. 3 No. 2

Volume 3, Number 1

Vol. 3 No. 1

Volume 2, Number 3

Vol. 2 No. 3

Volume 2, Number 2

Vol. 2 No. 2

Volume 2, Number 1

Vol. 2 No. 1

Volume 1, Number 2

Vol. 1 No. 2

Volume 1, Number 1

Vol. 1 No. 1

Cover Article: Defining HIV and SIV reservoirs in lymphoid tissues